David Feinberg shared their story and experiences with us recently and you can find our conversation below.

Good morning David, it’s such a great way to kick off the day – I think our readers will love hearing your stories, experiences and about how you think about life and work. Let’s jump right in? What is a normal day like for you right now?

I retired from 50 years of teaching at the University of Minnesota as the longest serving Art Professor, but now I am working just as hard as ever. Six months ago, I started working on my memoirs. At almost 82 years old, I exercise at a gym almost every day. When I was teaching at the university, I was lucky to have time to exercise two to three times a week. Since I had to give up my university studio to new faculty members, I have been working on adding and setting up an extension to the back of my garage for storage and a drawing studio. I am still organizing my daughter’s former room to be a painting studio.

I continue designing retreats and lectures. They are original designs based on my current thinking. I spend around two months on each one. Every day I work a little bit on the new lectures, retreats, and on my memoirs. When I have free time, I work on art in my incomplete studio, but memoirs take precedence until my creative spaces are finished. I also religiously do Sudoku and Cryptoquip every morning as a wake-up call to set up my cognition for the rest of the day.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

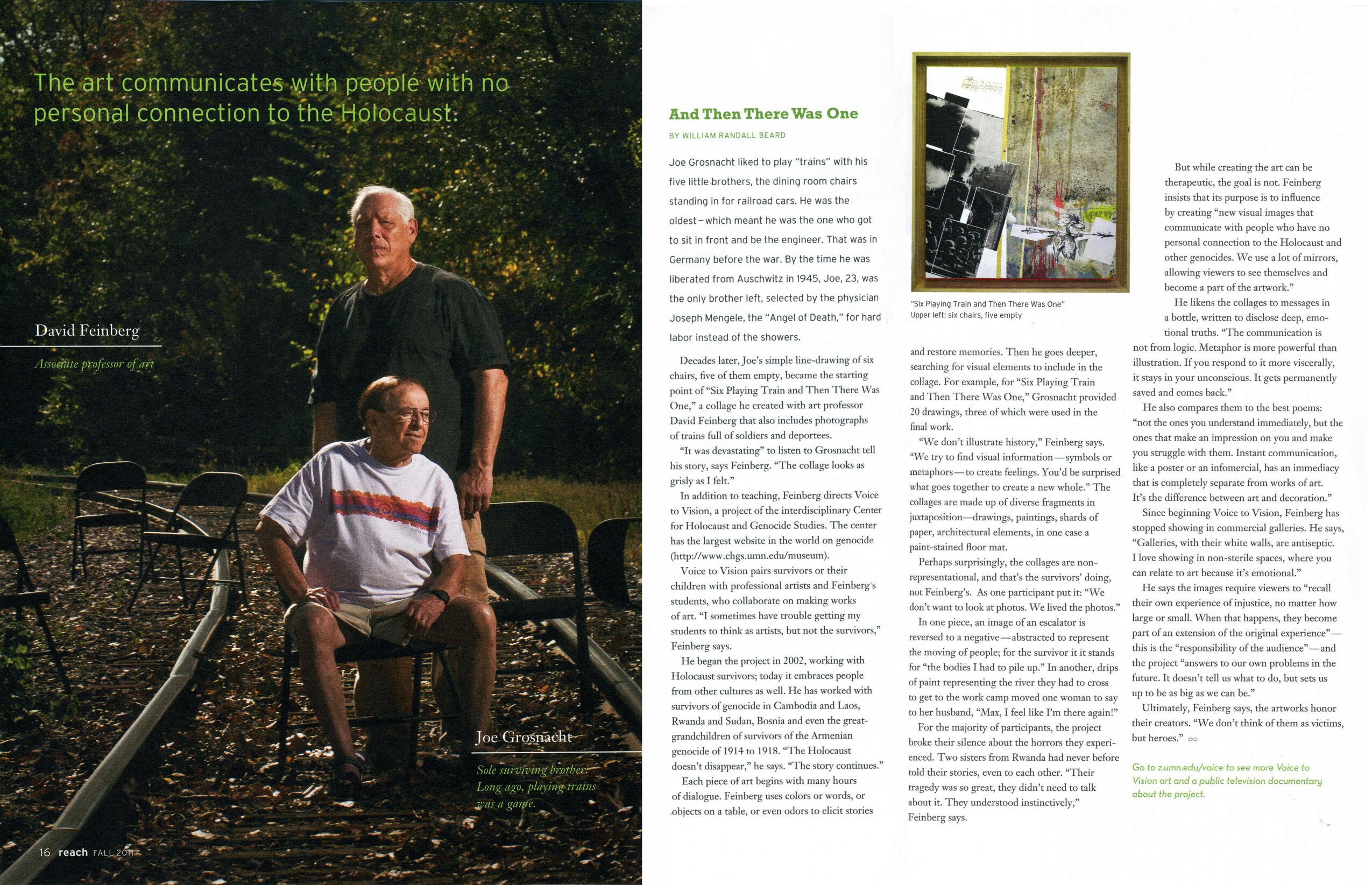

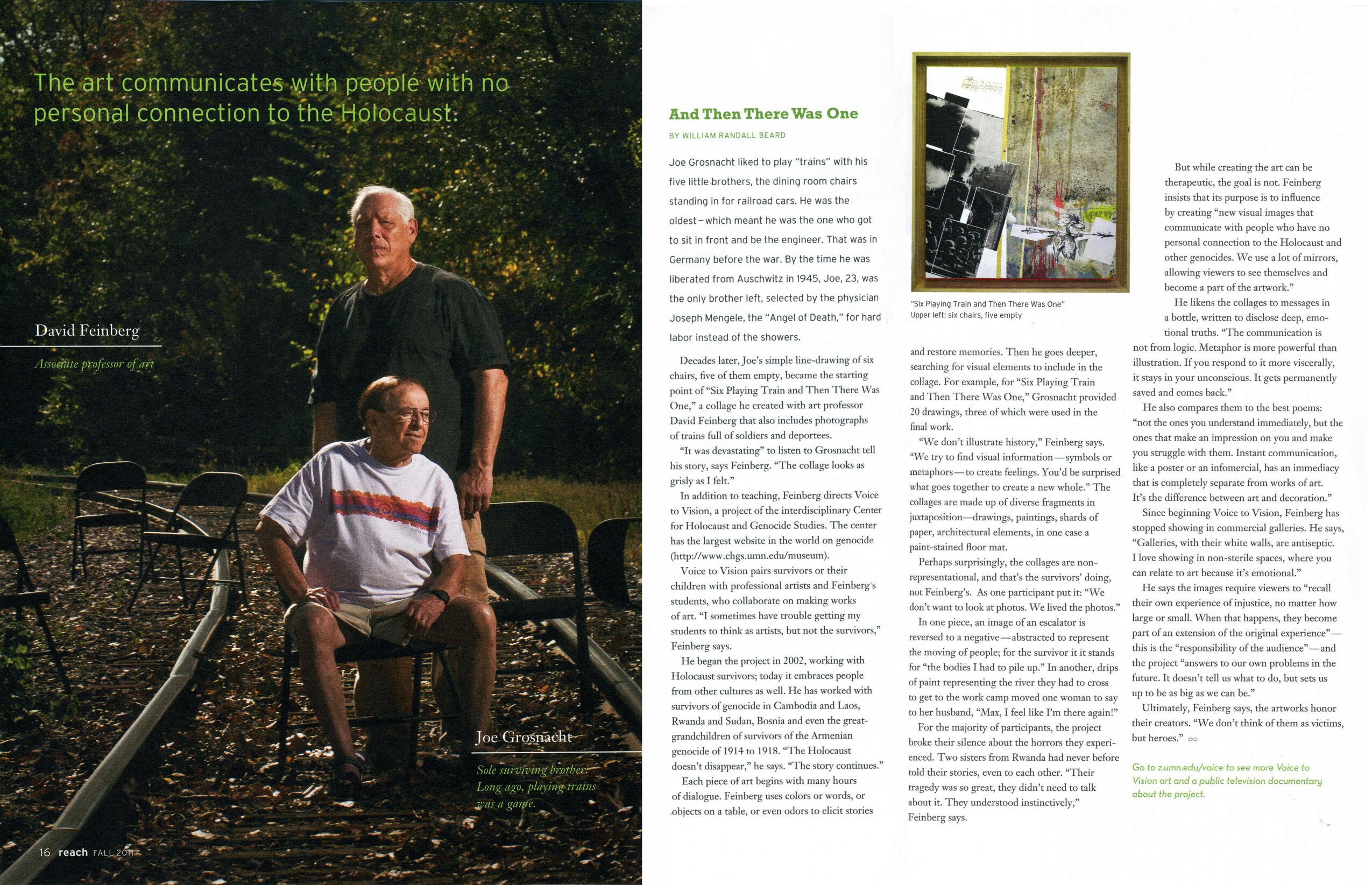

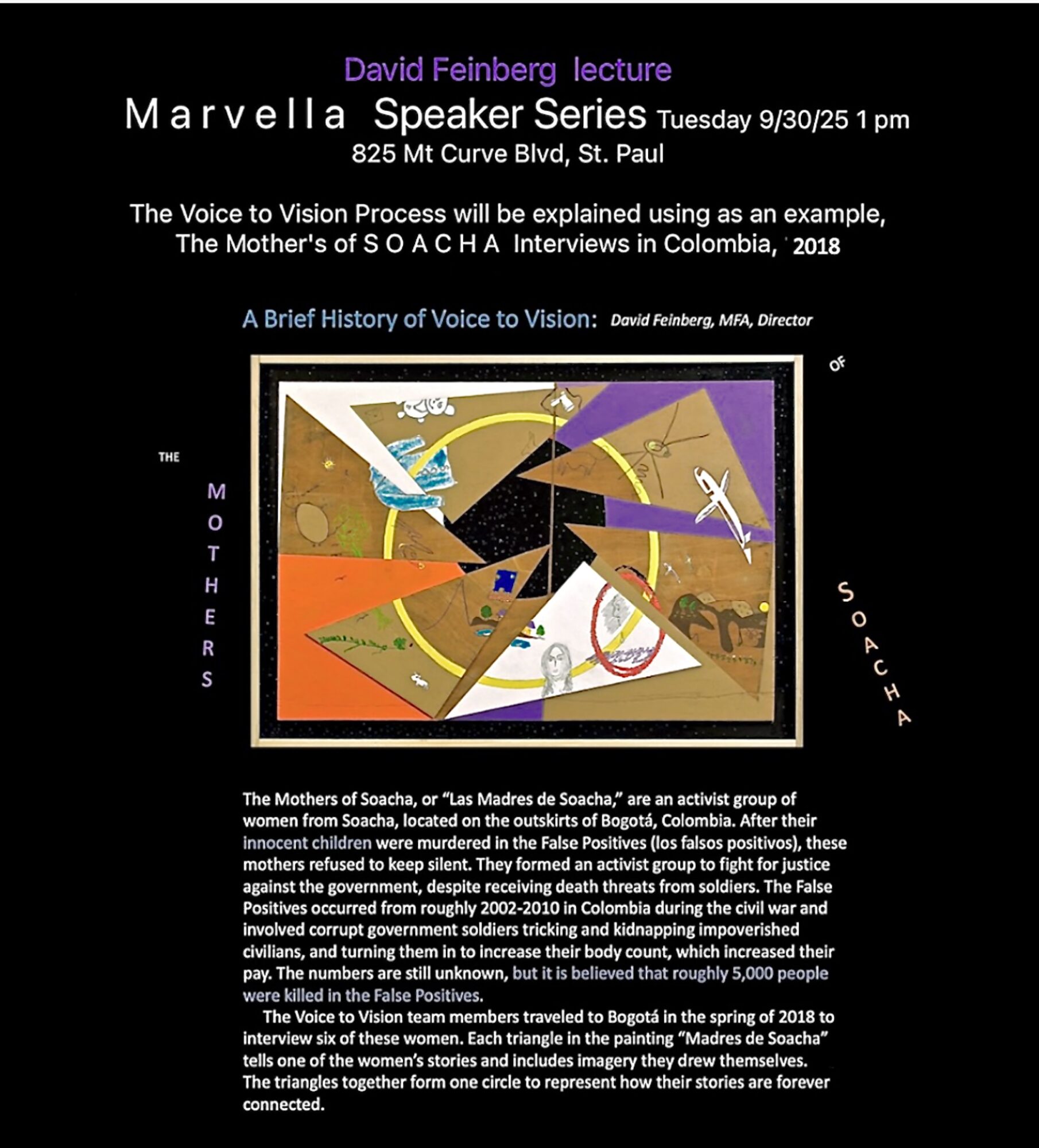

FEINBERG, David, is a Professor Emeritus of drawing and painting from the Art Department at the University of Minnesota. Retired after fifty years of teaching in 2021, he was the longest serving professor in the history of the Art Department. He is also the founder of “Voice to Vision”, a collaborative art project that also features video documentaries that record the process of survivors and witnesses of genocide and human rights abuses from four different continents. These artworks have been displayed nationally and internationally in universities, museums, and art centers since 2003. Upon retiring from the Art Department, he donated the entire 21-year collection of 104+ artworks to the Center of Holocaust and Genocide studies at the University of Minnesota, where he continues to actively work on the project.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/163988

He has received the C.E.E. Distinguished Teacher of the Year Award, the University Board of Regents Outstanding Community Service Award, the University of Minnesota President’s Multicultural Grant, the Grand Challenges Research Project: Social Justice; the Office of Public Engagement ACTION Grant and the CLA Hub Community Residency Grant and the 2024 President’s Award for Outstanding Service, University of Minnesota.

Okay, so here’s a deep one: What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

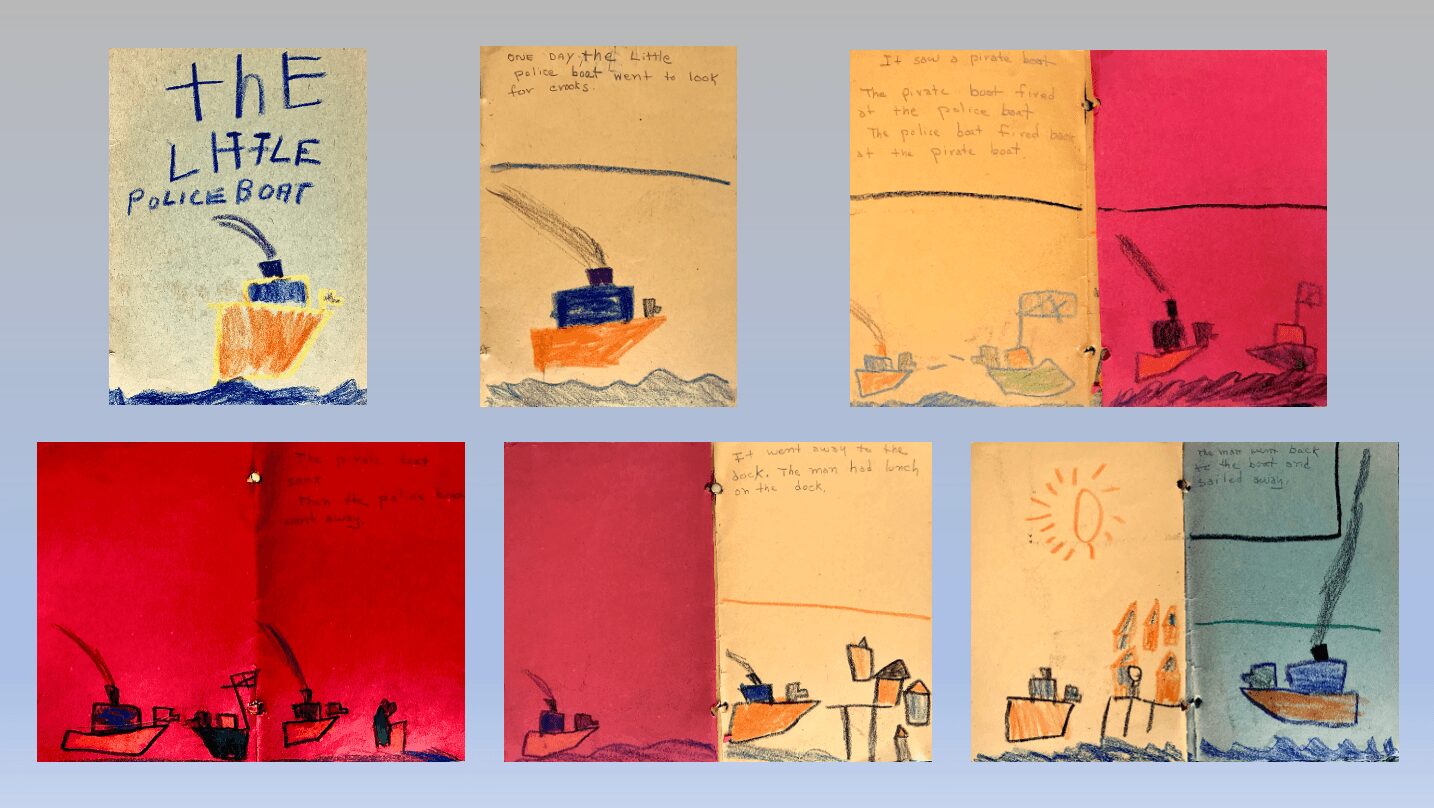

My earliest memory of feeling powerful was when I created my first remembered artwork, a crayon drawing that I did at the age of 3 ½, when I was bedridden. It became part of a 4-page book that my mother folded out of construction paper.

It was the power of self- expression. I had my mother write the simple words of the story.

I drew a battle between good and evil in the form of a police boat encountering a pirate ship. A police boat public tour our family attended on the Hudson River in New York around 1948 inspired me. On the pirate ship’s flag I made XX’s, thinking it represented the overlapping N Y on the New York Yankees caps. Being from Brooklyn, the Yankees were the Brooklyn Dodgers’ arch enemies. Even as a child I felt aware that something terrible was in the air. Holocaust survivors and other immigrants from all over the world filled my Brooklyn neighborhood. That was Brooklyn I was brought up in, with no distinct ethnic or religious majority.

Power of expression has a responsibility to be used wisely and never for manipulation.

I continue to use it to this day. Artistic expression is the search for meaning in a world gone astray. Artists should make this power available to the public and let the chips fall where they may.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

In the spring of 1966, I took a painting class at SUNY-New Paltz. The university had invited Philip Guston as a guest lecturer. The informal painting room at New Paltz, where Guston was scheduled to speak, was totally filled with students like a New York City subway platform. Outside the classroom, people jammed the halls trying to absorb the information that Philip Guston talked about. He had sat on the model stand, chain-smoking cigarettes as he spoke. I sat right next to him. He consumed numerous cigarettes while speaking for nearly four hours. He went through, perhaps 4 packs. His lecture proved to be the best, most impactful talk I’ve ever heard. It literally changed my whole life. It was the first time an artist spoke of his own fears, struggles, and concerns that I had worried about but previous held in.

While Guston spoke, I recalled seeing a chrome-plated canvas plier at a local art store, which is a metal tool designed for stretching canvas. I needed a canvas stretcher tool, and I had $10 in my pocket. Since it looked like the Guston talk was coming to an end, I wondered if I had time to run down there and buy the canvas plier or should I spend my $10 partying with the volleyball team. Was I going to become an artist? Or maybe, instead, I’ll become a Phys ed teacher like the rest of these sports guys. I was a health enthusiastic bodybuilder who had won the Jr. Mr. Metropolitan New York contest a few years before. The chain-smoking Guston was very unhealthy. He shook while talking. I’m thinking: “my God, he is the most brilliant person I ever encountered,” but he paid the price for staying true to himself in the art market while dealing with all the demanding pressures of the galleries and museums. I’m asking myself: do I want to pay that price? Do I want to wind up like Guston, with all the tensions that he coped with, or do I want to be a gym teacher? I thought nobody else who was that famous, talked about things that I was asking myself.

No teacher I ever had studied with, talked that way, therefore convincing me to go to the art store and be an artist. I got there 5 minutes before they closed, and I bought the stretcher plier which I took with me everywhere. Now I keep the canvas pliers up on a shelf on display as an omen or talisman to remind me that I almost rejected the art path even though it had been my whole life since I was 3; I almost left art until the Guston talk reaffirmed my life’s direction. My thinking was that: Art lasts forever and you get better as you age but not so in athletics. I concluded that I could still be healthy and be an artist, by avoiding the negative tensions of the art world. Education and awareness became more of a priority for me than fame!

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. What’s a belief or project you’re committed to, no matter how long it takes?

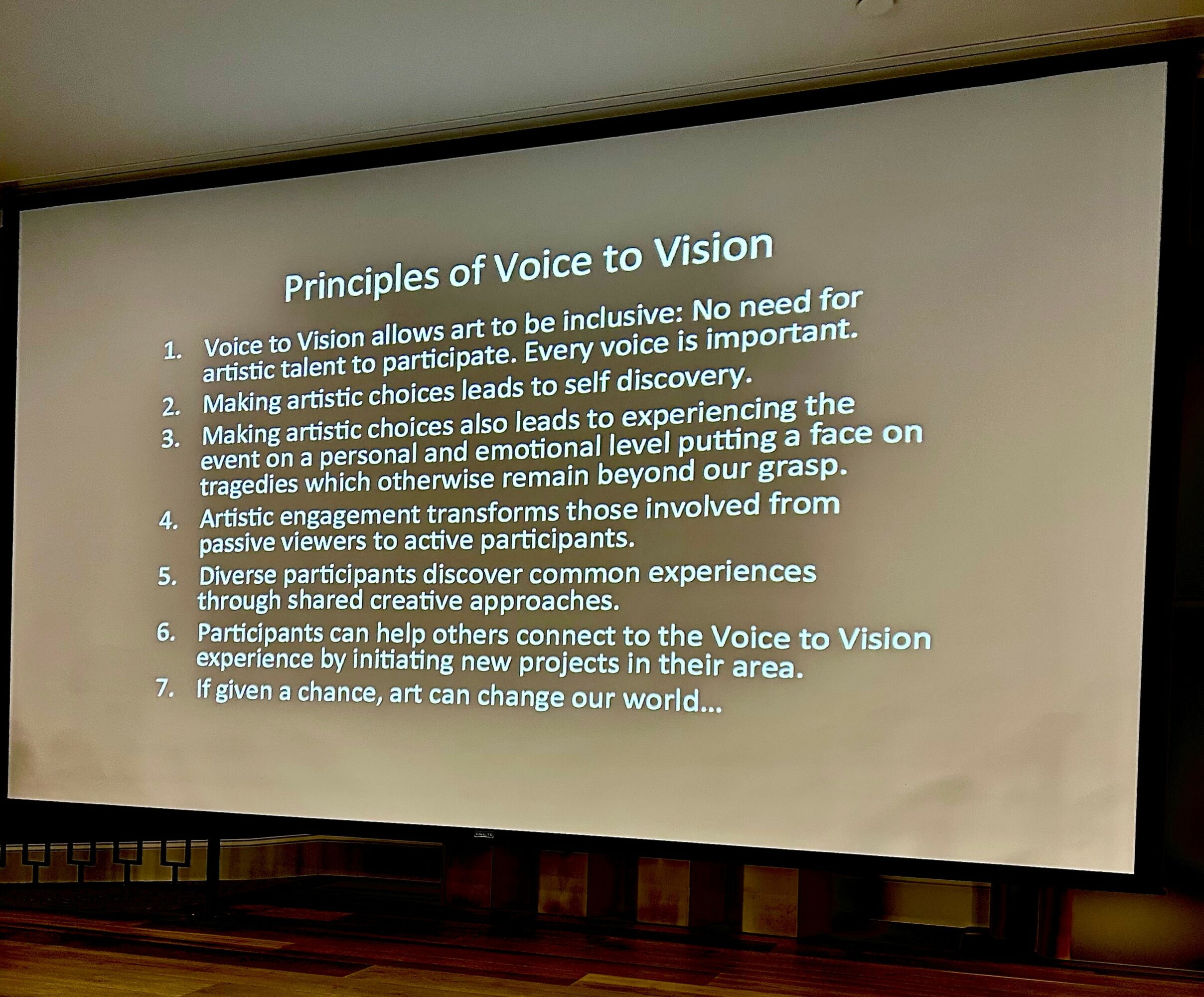

When I make art, I feel I am identifying problems and having a significant insight. Can non-artists experience this? In 2002, I developed a project called “Voice to Vision” and proposed it as a partnership with Dr. Stephen Feinstein, Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide studies. He accepted it immediately. Voice to Vision is a multicultural, intergenerational, interdisciplinary, and collaborative project, concerned with artistically telling the stories of genocide and human rights. The storytellers are survivors, witnesses, and/or activists, who work with a team of artists. The storytellers, who were victims or eyewitnesses, actually create the imagery and do the artwork with the help of an art team. Over the past 23 years, we’ve collaborated with storytellers from four continents and worked with more than 200 participants.

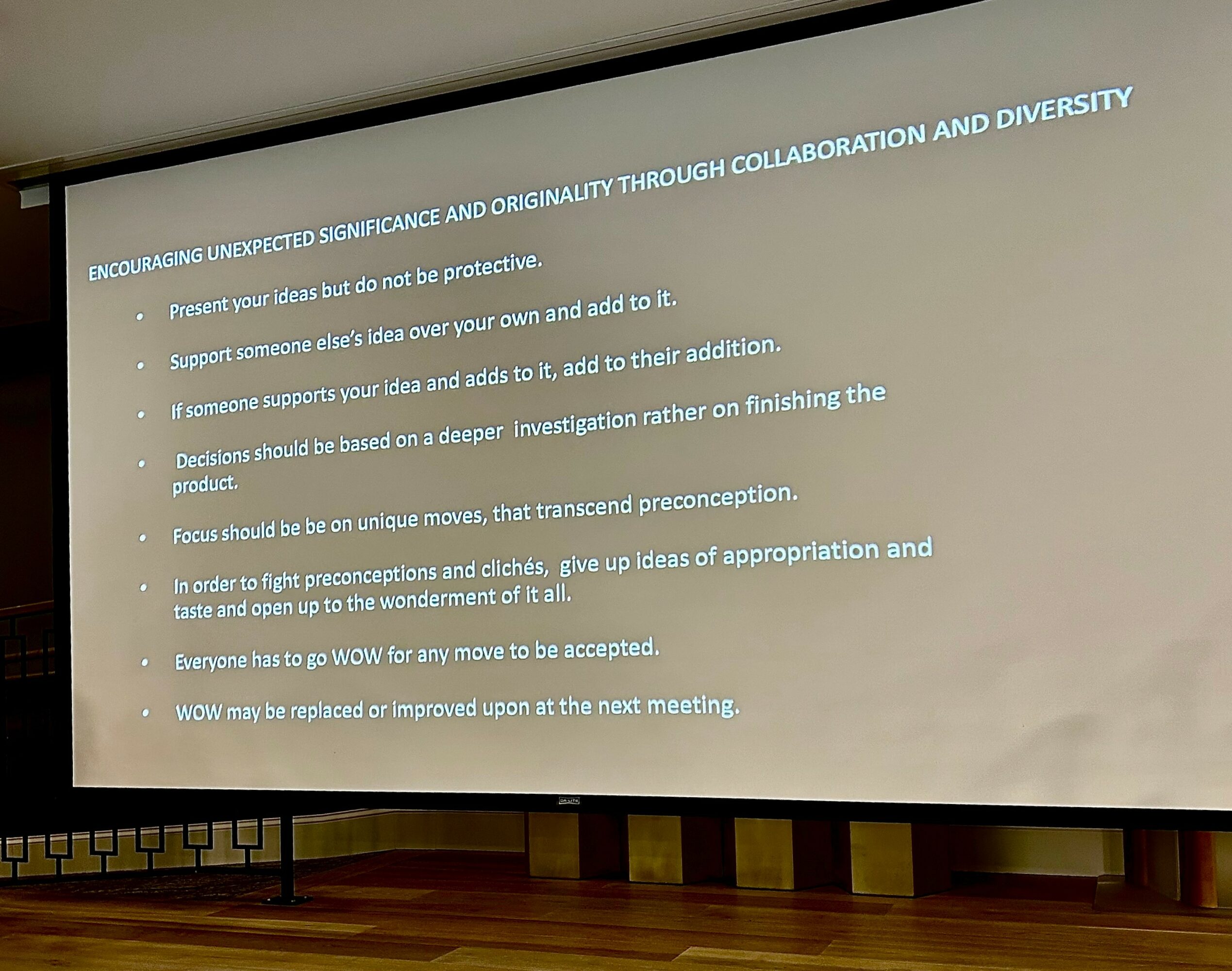

Meeting 4 or 5 times a month, It takes up to a year and a half to complete a project. Each move in the making of the artwork is discussed and it doesn’t become a reality until everyone in the group goes WOW in agreement. Since ideas for the moves become modified and changed many times over in discussion, no one could have predicted the final significant outcome. The distinctive moves have sparked engaging discussions that people want to continue and not end fast. The participants take these ideas home, tell their friends and relatives about them, and reflect on them for future input when the group meets again. Everyone who participates, has their Artistic DNA permeating the project, creating intense visual presence.

It is the goal of the Voice to Vision project to inspire others to use the tools of dialogue and the visual arts to investigate, recover, and protect their own indigenous narrative and emotional experiences. The art pieces also educate audiences by personally connecting them to crucial moments in history and by stimulating discussions

Thank you so much for all of your openness so far. Maybe we can close with a future oriented question. What do you understand deeply that most people don’t?

Unexpected Significance is the antidote to unrecognized conditioning and the key to originality.

If you ask artists today if they are original, personal, and independent, the overwhelming majority of them would answer, yes, very much so. They wouldn’t weigh the consequences of conditioning on their response. The drive for recognition and financial independence from continued sales can significantly shift priorities away from personal and spiritual concerns. Even if one is very aware of the problem, repeating seductions can have a toll on one’s ability to remain independent.

Experiencing Unexpected Significance is a key to insure originality. It is why experiences are remembered, talked about, and stored in one’s unconsciousness. In sports it occurs in the upset or when a record is broken. In comedy it is in the form of a punchline that wasn’t expected. Jamming in music is the process of finding the unexpected. When completed works of art succeed, they foster a mindset that any significant or surprising experiences will ultimately influence future artistic creations. Trying to remember the new experience is not necessary, as it happens automatically, thus becoming stored in one’s unconsciousness, waiting to reappear whenever prompted.

Being personal and original means that you have something to express that only you know about and are willing to share, searching for unknown structures that convey its destination. In the arts, one can go sideways, repeating variations of past successes or fashions that are in vogue. The way out of this stagnation or temporary success of being a follower, is to go in a direction of the unknown. This means something has stopped your daily routine without being understood. You sense its importance, even though you can’t quite explain the reason. It may not be immediately useful, but your unconscious memory will store it with other experiences similar to this one and they will accumulate. In the future the experience may appear again by an accidental prompt. Although it may initially feel wrong, taking on this new prompt will start a journey of ideas that ultimately leads to originality, the personal, and independence. Your artwork should be just as unique as the original unexpected s experience.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://conservancy.umn.edu/communities/01752c92-93f5-4b48-9b68-1dac573e40ca

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/feinb00

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/david-feinberg-98271616/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/VoiceToVision/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZVGChtPc-LmgceAhw1_ifg/videos

Image Credits

Paula Pergament

Elizabeth Feinberg

Kimchi Hoang