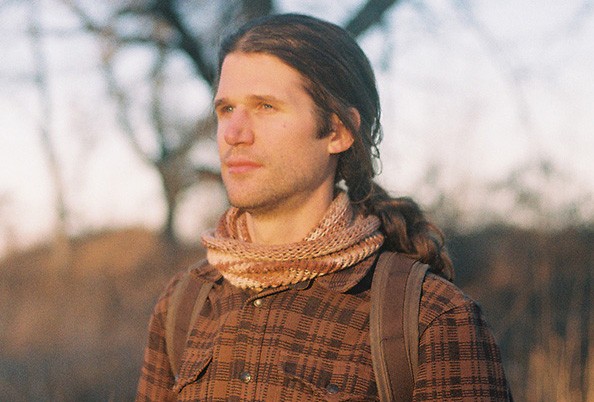

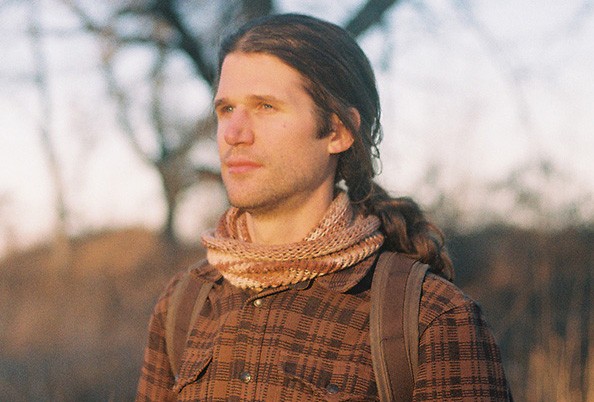

Today we’d like to introduce you to Kenan Serenbetz.

Hi Kenan, so excited to have you on the platform. So before we get into questions about your work-life, maybe you can bring our readers up to speed on your story and how you got to where you are today?

I am a musician and composer, and I write and perform music that examines our relationships with other-than-human beings. To do this, I take cues from many forms of pre-industrial folk music, trying to synthesize different musical elements in order to find a sound that is representative of and deferential to our upper-midwestern landscape.

I began as an improviser, studying jazz and saxophone. I feel very fortunate that I studied jazz, because it encouraged me to find my individual voice and seek technical and theoretical understanding. Although I eventually found that the constraints of the genre were not a good fit for my music, the knowledge and flexibility I gained allowed me to more easily move between many varied forms of music. I also met my closest collaborators, Alec Watson (of DPCD) and Ethan Parcell through jazz. Our collaboration and friendship is a consistent joy and inspiration , and my music will forever be in conversation with their work.

As I left the jazz world, I investigated a variety of music, searching for a sound with a relatively flat and meditative arc and delivery rather than the bombastic peaks and valleys of the other music I had been steeped in. I felt particularly compelled by old field recordings of indigenous and more explicitly land-based cultures, as well as medieval chant and polyphony. I also realized that my music would fall somewhere between composer-performer and singer-songwriter; I would write the words and sing the songs in the first-person, but musically the structures and material would draw from a wider range of sounds, even while following a basic song form. I also began to experiment with different instruments, searching for acoustic sounds related to my European-American culture that were capable of complex harmony while being relatively free from strong genre connotations. Detuned banjo, harmonium, pump organ, autoharp played like a zither — all of these instruments are related to my cultural identity and with some tweaking can sound more anonymous and ancient.

In the summer of 2014, I spent a few months in France with Marcel Pérès, an innovative musicologist of plainchant. I was studying chant with him while filming his work for a documentary I hoped to create about him. However, while there I contracted a virus that caused nerve damage, and ended up with vocal paresis, or paralyzed vocal cords. When I returned stateside, I was unable to sing or talk without great pain. Unable to perform and largely unable to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by urban life, I had to make major changes.

Over the 3 year recovery, I continued to compose, but spent the majority of my time learning to identify the plants of my home state, and coming to know their virtues and habits and stories. It was a very difficult time, but it was also a great gift. I came to understand the vast amount of life with whom we share our planet. I connected the sound of the field recordings I revered to the deep relationships those musicians have with their surrounding flora and fauna. I knew that cultivating this relationship in a time of global climate catastrophe was for me a spiritual necessity. Understanding the natural history of the land we live on and how to support its biodiversity is one of the keys to creating a livable future.

I also think that in secular culture there is a distinct lack of spiritual specificity. Many people find spiritual fulfillment in nature. Taking this further, I believe that as a species with a great deal of power, we must become stewards. Looking with wonder at birds and flowers is important, but an understanding of why that species is where it is and what it indicates about the health of the ecosystem is integral to confronting the unknown mysteries of life and the ways that the divine weaves itself through our existence. It is my great hope that my music can provide an avenue to that depth of relationship, and to be a voice for those beings that do not speak the human tongue.

I’m sure you wouldn’t say it’s been obstacle free, but so far would you say the journey has been a fairly smooth road?

The greatest struggle thus far in my artistic career was my vocal paresis. All at once, my instrument became unfamiliar, inaccessible, and extremely painful. Paresis occurs when the nerves controlling the vocalis muscle are damaged. The vocal folds sit slack, and the extrinsic muscles hyperfunction to bring the vocal folds together. The extrinsic muscles work so hard that they become extremely tight and painful. I had about an hour of voice use before my neck and jaw would burn with muscle pain. I was working in the service industry at the time, which required me to use my voice, and so whatever time I wasn’t working I was on vocal rest. I wrote notes and used voice assist software to communicate with friends. The nerve damage slowly healed, but I was left with muscles that were habituated to hyperfunctioning, which required further healing. Music had been my guiding light since middle school. The uncertainty of my musical future, the physical pain, and the social isolation were overwhelming. I eventually ended up with over 30 aphthous ulcers (stress-induced) in my throat, and was unable to eat solid food! At this point, I flew home to my family to seek out more specialized medical attention. On the flight home, I saw a musician fingering through some passages of music across the aisle from me. I spoke with her, and told her about my situation. She recommended a voice teacher named Matthew Ellenwood (they/them) in Chicago, who is the reason I got my voice back. Matthew is an incredible voice teacher, musician, theater director, the list goes on and on, and I am forever indebted to them for their help to me.

My recovery took about 3 years, from the onset of the paresis to the moment I was 100% recovered and singing-fit. This period was the most difficult in my life thus far. There are so many friends and family and others who supported me during this time, and I am forever grateful to them. Music, my vocation and emotional outlet, had been essentially cut off. The mental health ramifications of all this were far-reaching, and something that I still deal with to this day. But, as it sometimes goes, if we can emerge from deep struggle we come back with new purpose, understanding, and strength. I had found a way in which I could live on this earth and do my small part to help heal the ills of our time.

I also became involved in many different communities and disciplines that are now a part of my everyday life in some way or another. I learned about the culinary and medicinal virtues of the local flora. I spent time in habitat restoration communities, learning about the ecology of the tallgrass region, how different plant species interact, and what factors dictate the health and biodiversity of ecosystems in our region. Most importantly, I spent a lot of time observing all of these factors and trying to draw connections between them.

For example, if you look at a distinctly midwestern species like the Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), there is a lot to be learned. Bur oaks are the dominant oak species in open areas in our region. They have thick, corky bark, which allows them to withstand the wildfires that were once far more frequent in our region. This bark is used medicinally for a number of reasons, namely for its astringency, which helps atonic tissues like receding gums, dental caries, diarrhea, etc. They also produce acorns, which are an abundant and highly nutritious food for humans and animals. The white oak family (of which bur oaks are a part) also host more caterpillar species than any other trees on the continent, and thus provide meals for countless species of birds and other critters. Bur oaks are the last trees to leaf out in the spring, and the relative density of their canopy allows a larger amount of light to filter to the ground than other tree species like maples. This allows spring ephemerals to complete their life cycles and store up enough energy for the next year before the canopy fills in. It also allows for specialized species, like yellow false foxglove (Aureolaria grandiflora) and cream gentian (Gentiana flavida), to grow in this distinct environment, and to create ecotones between the sunnier and shadier areas where more prairie or woodland species will thrive. With colonization, as land was stolen from native tribes and white settlers imposed their own ideologies upon the land, fire was suppressed, as it was considered destructive. However, native tribes burned vast swaths of prairie and savannah for millennia, which preserved these distinct plant communities and encouraged their growth. When you see an old bur oak tree now, look around. Are there many other large old oaks around? Are there a great deal of young trees like maples and basswoods growing around it? What plant species are underneath? This bur oak could be standing on land that was once savannah or even prairie, and due to lack of fire it now appears to be part of a forest. It will eventually be outcompeted by the shade of less fire-resistant trees and die, along with the flora that existed underneath it if they haven’t already disappeared.

I have only scraped the tip of the iceberg on one species that lives in our region, and I’m no biologist. If you think about the myriad plant and animal species that live here, and how each one of them has a similarly complex and multifaceted story, and how each individual within the species has its own unique life, you can see how it becomes impossible for a human mind to fully comprehend. This vastness is inspiring and life-giving, and begs the question of what OUR role is in the ecosystem. What cross-species interactions do Homo sapiens have, and how does that function within a healthy ecosystem? It is easy to be cynical and think of us as a cancer on the earth, but as I mentioned earlier, human-caused fire is an indispensable element in preserving the biodiversity and health of this land. We are stewards, and stewardship is directly tied to our well-being.

Without my voice issues, I may have never become aware of this. It gives me purpose and hope for our species, that we can be a force for good, and that it is not too late to create a future in which climate catastrophe doesn’t decimate us and all our other-than-human brethren. In losing my voice, I found it, and though it was difficult, I am eternally grateful.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

I write songs about seeing the divine in the natural world. I spend a great deal of time learning and observing our native landscape and all the beings it comprises, and I try to code these impressions into my music both sonically and lyrically. Ideally, I would like my music to occupy a space where it functions as sacred music for a more animistic and/or ecologically-minded populace. Musically, one of the main strategies I employ is writing contrapuntally, rather than writing chords and a melody. Nearly every part in my music has its own melodic shape and contour, and is meant to work in tandem with other melodies to create a texture of living parts. This is meant to mimic an ecosystem, in which every being plays a crucial role in the harmonic and rhythmic fabric. This also allows my voice, while still being the lead melody, to exist within a texture of many other melodies, evening out the sound hierarchy and representing the human role in the ecosystem – not one of dominance but of symbiosis. I also try to create rhythmic cycles where there are few and irregular strong beats. The rhythm of a landscape does not exist on a grid with regular markers. In the midwest in particular, the landscape is flat and undramatic.

Lyrically, I reference many sacred texts, as well as poetry that explicitly names and interprets local phenology and ecology. The imperial anthologies of waka, namely the Kokinshu and Shinkokinshu, have been particularly helpful. They are brief, and filled with powerful images relating to a greater symbology of phenological events: the belling of the deer in autumn, the plum and cherry blossoms in spring, and the first snow in early winter. I strive in my own words to create a bioregional cosmology of other-than-human beings, and to place any autobiographical information against this backdrop.

I released an album in 2021 called CLEARING, which was my first published iteration of this compositional style. The album focuses in particular on the experience of the voice injury and learning about my local ecology for the first time. It features the voices of Maren Day and Morgan Kavanagh of Bad Posture Club, who are close friends and collaborators. I am proud of this album, which can be found at any of my links below. I am working on the next installment, which is in the early stages of recording.

The crisis has affected us all in different ways. How has it affected you and any important lessons or epiphanies you can share with us?

I don’t feel like I have much to say about COVID that hasn’t already been said. I think a lot of people found some sort of new outlet or hobby when they were stuck in the early stages of quarantine, and I was no exception. For me, it was writing chorales inspired by J.S. Bach. It is a very fun exercise to plug my harmony and ideas into an existing form. It also challenges me to have a different conception of melody. I hope to perform some of these in the future.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://kenanserenbetz.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kenanserenbetzmusic/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kenanserenbetzmusic

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRmTBpdDcVelvK407v825DA/featured

Image Credits

Urian Franco

Elena Stanton

Kenan Serenbetz