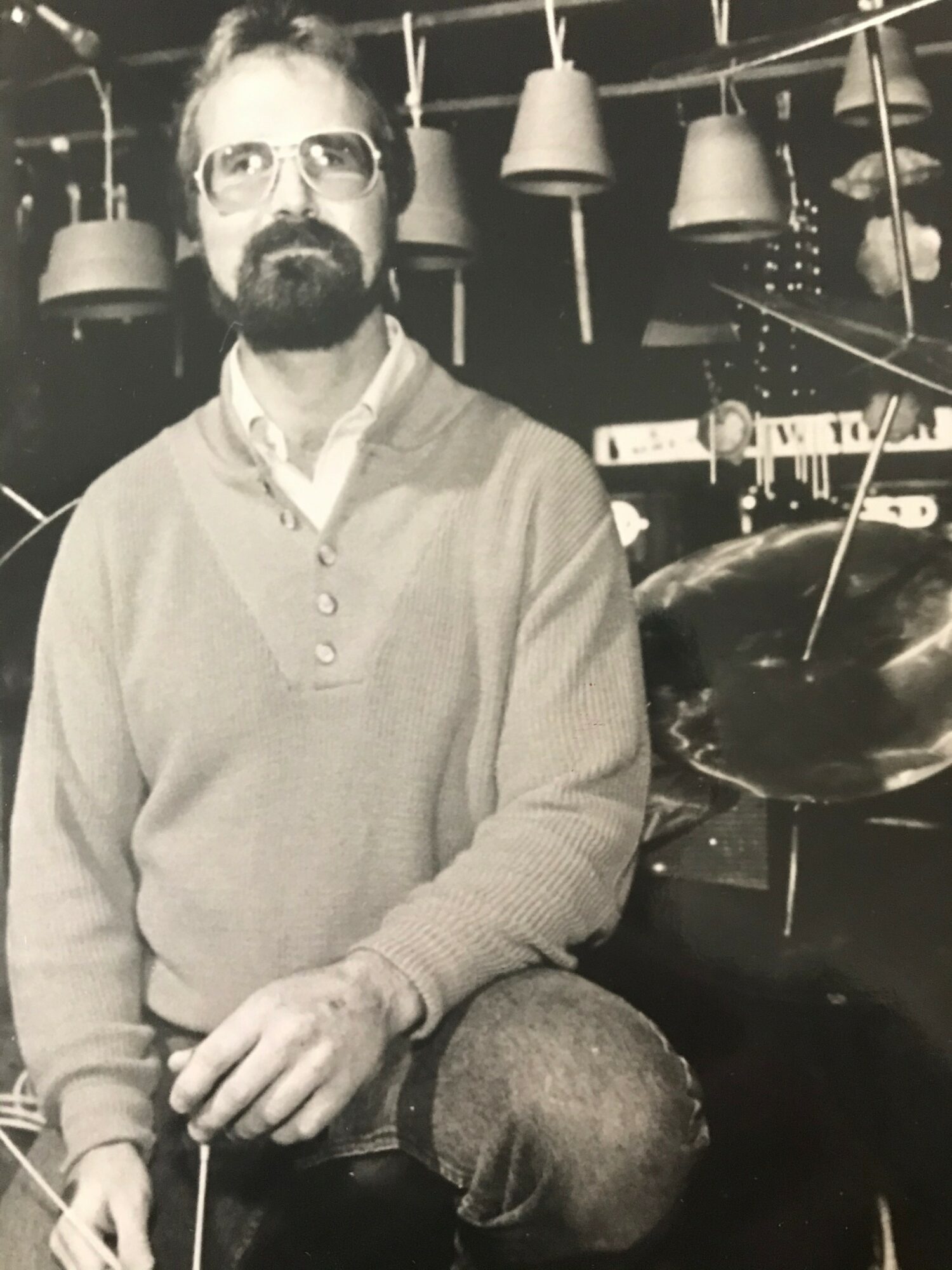

Today we’d like to introduce you to Paul Dice.

Today we’d like to introduce you to Paul Dice.

Hi Paul, thanks for sharing your story with us. To start, maybe you can tell our readers some of your backstory.

My interest in music began in elementary school. After hearing “March of the Toys”by Victor Herbert from the movie Babes in Toyland, I decided it was time for me to learn to play a brass instrument, so I chose the trombone. But even back in those early days, I was already curious about music from other places. I spent many hours looking at my backyard through a big picture window in our living room. My secret wish was that aliens from another galaxy would zoom by, pick me up in a spaceship and take me to their planet so I could study their music. But, of course, nobody ever came. I later realized that there was music from cultures all over our planet that I knew very little about, so I shifted my focus. Every time my father asked me what I wanted for Christmas or my birthday, I would tell him to go to the local record store and randomly pick out an album from the world music bin. It was through these albums that I was introduced to Japanese, Chinese, and Indonesian gamelan music. These three musical traditions continue to influence my music along with movements and sounds of nature and my years of playing in rock and jazz bands. Due to the sporadic nature of touring, in 1976, I decided to commit myself to composing and attending the Boston Conservatory. At the Conservatory, they primarily taught me about contemporary European trends in composition. Since the music I heard in my head and wanted to compose was full of peaceful, intertwining melodies, I was still unsure of how to move forward. But ten years later, I began studies and a lifelong friendship with California composer Lou Harrison. Lou was the first to successfully combine Asian and Western styles in his compositions. At our first session at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in Florida, he handed out three scores for us to study – one Chinese, one Japanese, and one Javanese gamelan. Within these three musical traditions were the answers I had been searching for. In 1988 I studied with Lou again, but this time at his home in California. After a month of daily lessons, staying in his guest room and eating his food, I asked about his fee. It was something he never brought up so I brought all the cash I had and hoped it would be enough. He simply asked me if I was wealthy. I replied that I wasn’t wealthy but wasn’t poor either and would be happy to pay him whatever he wanted. He told me that the Atlantic Center for the Arts had paid him enough and that he didn’t need any money from me. He told me that one day I would have the chance to help someone out in a similar way, and that would be payment enough. I couldn’t imagine that I would ever be in a position to help someone else out like that, but four years later, I had that opportunity. I was invited to be a part of a music delegation that traveled to China and Kazakhstan to study the music of the minorities. On my second day in Beijing, I met Gao Hong, a top pipa player who played for me and allowed another delegate to film her. What Lou had said to me finally made sense. I asked Gao Hong if she’d ever want to come to the US to do a tour. She immediately agreed and I spent the next year and a half lining up a 10-city tour for her. It was something I had never done before. But I wanted to continue Lou Harrison’s legacy of kindness. Gao Hong and I corresponded through a translator and fax machine and eventually fell in love and married. We celebrated our 28th wedding anniversary last May. So Lou Harrison’s kindness and generosity had major impacts on both my musical and personal lives.

Being part of the delegation inspired me to start a nonprofit organization that promotes intercultural friendship, understanding and interaction through activities in the performing arts. For the last 30 years, I’ve presented, booked, and commissioned projects from top musicians and dancers from Asia, Africa, North and South America, and Europe, and viewing firsthand their supreme artistry and commitment to their music and cultures has greatly influenced the music I compose.

We all face challenges, but looking back, would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

As a composer I am constantly seeking out opportunities to have my music performed. Most opportunities are open to composers all over the world, so the competition is stiff. I recently learned that the standard rejection rate for most opportunities is between 95 and 98%. So composers need to be thick-skinned and not take rejection personally. Fortunately, I’ve already had my music played by wonderful musicians in China, Russia, and throughout the U.S., So I savor these successes and continue to send out my pieces everywhere I can.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

The music I compose is primarily inspired by movements and sounds of nature and practices used in other cultures and art forms that I adapt for use in my own brand of music. Some of my music also has elements of rock and jazz from my bass-playing days earlier in my life. Part of my rock influence includes a preference for composing shorter pieces closer in length to classic rock songs than a symphony. I also enjoy composing for foreign or unusual instruments and have composed for traditional Chinese instruments, Japanese hichiriki, and taishogoto, Javanese gamelan, Philippine kulintang, harmonic singers, metal sculpture, and western orchestras, chamber ensembles, and soloists.

Fatherhood has been my life’s greatest joy and I am most proud of how my daughter, an only child, has found her place in life so quickly and accomplished so much in such a short period of time.

We all have a different way of looking at and defining success. How do you define success?

I feel that if you are happy and enjoying your life, you are successful.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.pauldicemusic.com. https://www.iftpausa.com

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCCbbY-qwCJTJqiqdqei_4QA?view_as=subscriber

Image Credits

John McLeod